Sam P. for Nov. 3

I will now own up to how profoundly my reading of the 1855 “Song of Myself” freaked me out.

I doubt that I’m alone in that reaction. The 1891-92 “Death-Bed” edition of Leaves of Grass seems to easily surpass other versions in terms of current availability. Together with the fact that the “Death-Bed” contains the last revisions Whitman was able to effect before his death, the “Death-Bed’s” prevailing presence has imparted to the text, at least to me, something of the character of an immutable literary monument. Given the compact recognizability of the opening of “Song of Myself,” this poem evinces this quality even more pronouncedly, making it rather like Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in terms of its succinct iconicity. Every ounce of that document’s language rings with a kind of engraved familiarity, a sense that the combined sounds—in their exact rhythmic sequence—deepen the meaning of the words themselves. We feel ever more strongly that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth” precisely because that sentence, and the semi-musical feeling of reciting it, will never perish from our American collective memory. That is the text; how could there be any other?

Imagine, then, that you read an earlier draft of Lincoln’s speech that opened with the phrase “Eighty-seven years ago.” Only so dramatic a change can illustrate how jarred I was when reading the first stanza of the 1855 “Song of Myself”:

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. (27)

Of course, the first line reads “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” in the 1891-92 Leaves (though the online Walt Whitman Archive reveals that this opening first appeared in the 1881 edition). Even if I assume incorrectly that the “Death-Bed” edition has long reigned as the form most widely circulated and readily available, I have at least Whitman’s own assertion, in the notice that opens the 1891 version, that he “prefer[s] and recommend[s] this present one, complete, for future printing, if there should be any” (148). If Whitman thereby guaranteed that this would stand as the “authoritative” Leaves, as Amanda Gailey notes in her “Publishing History” of the collection, my own experience with the “Song’s” first stanza has ratified this definitiveness.

Why should it matter, though, that this final form of the poem’s opening stands so strongly in my memory, or my country’s? I think the answer lies in the way in which the short line “I celebrate myself” forces me to confront my internal construction of Whitman as a “literary personality,” a figure almost deified in our willingness to use certain texts, like the opening of the “Song,” as talismans testifying to his greatness. Even though we have traveled to D.C. and faced the sheer material proof that Whitman lived, wore glasses, had hair, etc. (I really wish, perversely enough, that those strands had come right out of his armpit), my earlier astonishment at seeing “I celebrate myself” in isolation, and my relief at now seeing it “completed” by its partner phrase, make me realize how strongly the “Great American” legacy of Whitman has taken hold of me. Can I ever really “love the man personally”—or, like Whitman’s from-afar infatuation with Lincoln, do I just have to wish I could?

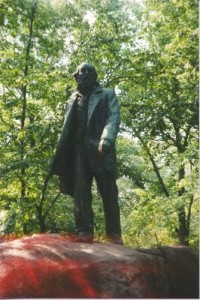

Not just a monument of words

(Image from http://www.mallowandgogo.com/gallery/slideshow.php?set_albumName=album01)

November 3rd, 2009 at 10:40 am

You definitely were NOT alone in feeling troubled with this version of Song of Myself. In fact, your last line made my brow furrow and lip tremble a little, “Can I ever really “love the man personally”—or, like Whitman’s from-afar infatuation with Lincoln, do I just have to wish I could?” I had been signing a few emails as Mrs. Virginia S. Whitman, despite the obvious (to me) suggestions that he was not attracted to women. Yet, as we are winding down this class, I think we are looking deeper into his meaning. Not only the meaning of his words, but his flow, his tone, his use of the language in a way that did not become clear to me until recently. Beautiful post!